Message from the Dean: Joining Mali at the Crossroads

July 8, 2013

New York Times reporter Lydia Polgreen introduced her article about the conflicts in Mali at the beginning of 2013 with the following reflection.

In modern times Timbuktu has become a synonym for a remote place. But the city thrived for centuries at the crossroads of the region's two great highways: the caravan route across the Sahara passed right by its narrow warren of streets, brings salt, spices and cloth from the north, and the Niger River brought gold and slaves from West Africa. Traders brought books, and the city's scribes earned their living by copying them out by hand. These manuscripts cover a vast range of human knowledge – Islamic philosophy and law, of course, but medicine, botany and astronomy as well. (Polgreen, New York Times, Feb 3, 2013)

In the language of the largest ethnic and language group in Mali, the bamana people, the word for crossroads is dankun, symbolized by the footprint of the dove: "X". Dankun refers to a place in a forested area where the human world and the spirit world meet. It is in such a place that acts of self-sacrifice for the sake of others can occur. That is, where "us and our future" take precedence over "me and my future."

Mali is now entering such a crossroads in which what might otherwise feel unfair to those who believe they have suffered most must be understood in terms of "us and our future" as a people. Without this kind of reciprocity, the danger of falling back into civil war and brutal reprisals is all too real. Let me begin this reflection with a short review of the relationships that have existed between Mali and the RCAH.

Mali has had a special place in the RCAH since the college began. Professor Candace Keller and I have been involved in several long term projects, including her photography digitization project and the study abroad program that Chris Worland and I have taken to Mali four times – the fifth would have been in summer 2012 when we had 17 RCAH students signed up and ready to go. In addition, two separate groups of Malian academics and religious leaders were at the RCAH for two weeks each in 2009 and 2010 to learn about the relationship between religion and democracy, and share with us their own multicultural traditions. In addition, several Malian artists have been guests of the RCAH, most recently hip-hop artist Koumandian Andre Keita (KJ). This summer the RCAH Lookout! Gallery is hosting “Mali On Our Minds” an exhibit of contemporary Malian fabric art, photography, and traditional Malian sculpture.

Dean Esquith, Chris Worland, and the Ethics and Development in Mali: Art, Culture, and Education study abroad group from 2010.

I have been teaching both Malian students and RCAH students in Mali since 2004, learning firsthand what has made Mali one of the more stable, albeit poor, democracies in West Africa. That is, until the coup in March 2012 overthrew the government on the 50th anniversary of its independence from France and 20 years after the creation of the Malian multi-party democratic republic. To make matters much worse, the vacuum created by the young, politically inexperienced military junta, led to bold and sometimes brutal actions in the northern part of the country by rebel separatists who have felt that they have been long mistreated by the central government and even more aggressive violence by Salafi jihadists coming from other parts of West and North Africa in hopes of providing a radical Islamic safe haven for Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

Roughly 400,000 Malians have fled their homes and land in the north of the country (about the size of France), some moving south to the capital Bamako, others to other regions in the southern part of the country, and others to neighboring Niger, Mauritania, and Burkina Faso. All of this has happened in just over a year. The resulting chaos and despair lasted until the UN authorized military intervention led by the French. The rebels have disassociated themselves from the jihadists and the jihadists have retreated from the major cities in the north that they had terrorized (Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal). An interim President of Mali has been appointed, a National Commission for Dialogue and Reconciliation has been named and begun its work, and a date has been set for Presidential elections in late July with more than 30 candidates now officially qualified to be on the ballot.

There are still UN peacekeeping troops on the ground and the identity cards that have to be issued to voters still need to be fully distributed. But there is a nascent political process. After 20 years of very modest political development, significant political corruption, and very difficult economic times that culminated in an unexpected coup and a humiliating set of military defeats by jihadists in the northern part of the country, Mali is at a crossroads. It could slip back into the weak democratic society it had become with one of the lowest voter turnout rates in Africa, or worse, it could be the target once again of extremists enforcing their own intolerant form of Sharia law. On the other hand, Mali could move in a more democratic direction. It could expand the participation of girls and women in politics, education, and civil society. It could rid the north of its archaic practices of virtual slavery for some minority groups by others. It could increase agricultural production and deal with the problems associated with severe poverty. And, it could determine what justice requires for those who carried out the rebellion and violated the human rights of many innocent Malians so that a dialogue of trust and a process of reconciliation can be established at local levels in Mali, not just on a national stage.

It is too early to tell which direction Mali will go. However, for the past week I have been meeting with a wide range of Malians and also others working in Mali to establish a new, more democratic society. It has been inspiring to listen to the youth. It has been sobering listening to older Malians who have seen Mali gradually slide into the current morass. And it has been enlightening to hear the many ideas, scenarios, and interpretations of Malian professionals, artists, and development practitioners.

Dean Esquith speaking with students in an American Studies course at the University of Bamako about the distinction between public and private higher education in the United States.

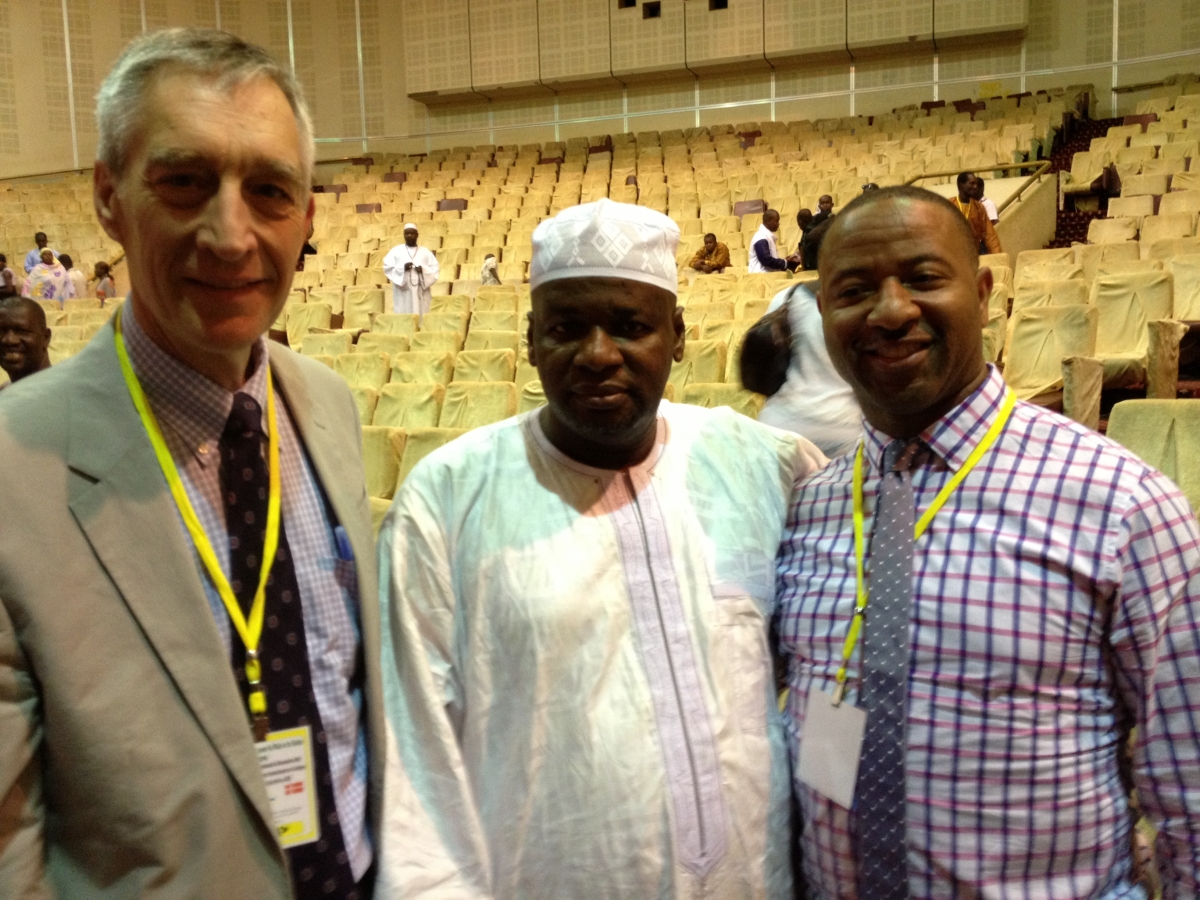

Dean Esquith, Imam Diallo of Torokorobougou, Bamako, and Professor Austin Jackson.

For example, RCAH Professor Austin Jackson and I were invited to present papers at the 5th Annual Conference on Peace and Tolerance from June 29 to 30 as part of the Conference on Peace and Tolerance in Bamako. This was the second time we’ve attended this West African event focused on the need for greater dialogue between Christians and Muslims. I was impressed with the range of views and the seriousness with which the delegates took their jobs.

Invited speakers to the Conference for the Promotion of Ethical and Spiritual Values among Christians and Muslims in Mali and West Africa: Strategies, Challenges, and Perspectives; organized by the Malian

Association for Peace and Tolerance, June 29-30, 2013, in Bamako, Mali.

After the conference, I met with the head of the Malian National Commission for Dialogue and Reconciliation who seemed to be open to the idea that local and regional dialogue forums be created so that the process is sensitive to the actual priorities of villages and small towns. This idea comes from Interpeace, another group now becoming active in Mali. They have worked successfully on long-term reconciliation projects in Somalia, Guinea-Bissau, and Libya and are now constituting a team in Mali with Malian leadership.

Then, I met with a group of Malian NGO leaders to discuss the political responsibilities of NGOs for the current crisis and what role they may play in new efforts at democratic political education, not just humanitarian assistance. Finally, Professor Jackson and I met with 35 college students and teachers in Kati at the Institute for Popular Education where we have held the RCAH study abroad program, followed by another meeting with 15 of the Malian members of the delegation who came to Michigan in 2009 and 2010 as part of a major exchange program on religious tolerance and democracy.

Mali Conference on Strategies, Challenges, and Perspectives for a Dialogue on Peace and Toleration. Second from left, Imam Diallo of Torokorobougou, Bamako, with representatives from Egypt, Cote D'Ivoire, and the United States.

There were other events and conversations during this busy week long trip, but you get the main idea: Malians are focused on the choices they face at this new crossroads and they are eager to talk about it with old friends like RCAH faculty and students. They are on our minds, no doubt, but there is a sense that despite the stress they are under, we are also on their minds. They remain the warm and welcoming people whom we have worked with in the classroom and on research projects. It is still not clear exactly when we will be able to resume these exchange and collaborative programs, but during this intense week, it became clearer to me that RCAH has a role to play in Mali, and Malians, I hope, will once again be working with RCAH faculty and students. This is how our civic engagement and study abroad programs should progress, through good times and bad, so that we can lend support to our partners when they need it and also learn from their challenges about how we might make progress here at home ourselves.