Finding a Voice, and Hauling Memories in Silence

April 2, 2019

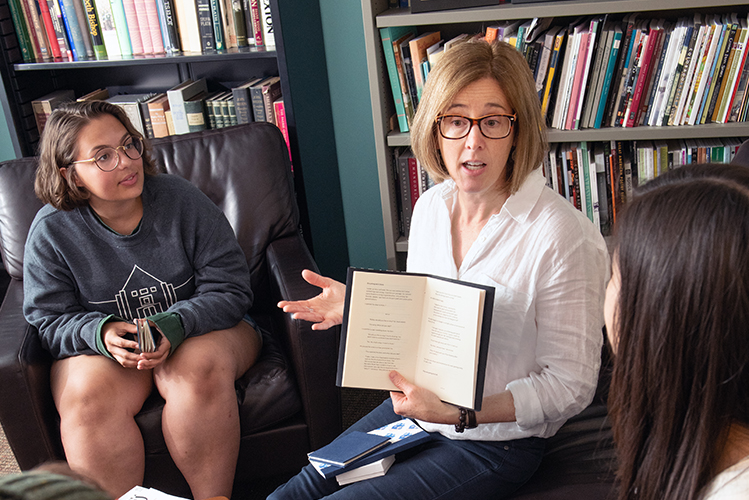

A National Poetry Month Interview with Cindy Hunter Morgan

Cindy Hunter Morgan (pictured center) is the interim director of the RCAH Center for Poetry and the author of a full-length poetry collection and two chapbooks. Harborless was named a 2018 Michigan Notable Book and the winner of the 2017 Moveen Prize in Poetry. Apple Season won the Midwest Writing Center’s 2012 Chapbook Contest, and The Sultan, The Skater, The Bicycle Maker won The Ledge Press 2011 Poetry Chapbook Award. She writes regularly for Murder Ballad Monday, a blog devoted to the exploration of the murder ballad tradition in folk and popular music, and her poetry has appeared in a variety of journals, including Tin House Online, Salamander, The Pinch, and West Branch. Visit her website: https://www.cindyhuntermorgan.com.

Cindy Hunter Morgan (pictured center) is the interim director of the RCAH Center for Poetry and the author of a full-length poetry collection and two chapbooks. Harborless was named a 2018 Michigan Notable Book and the winner of the 2017 Moveen Prize in Poetry. Apple Season won the Midwest Writing Center’s 2012 Chapbook Contest, and The Sultan, The Skater, The Bicycle Maker won The Ledge Press 2011 Poetry Chapbook Award. She writes regularly for Murder Ballad Monday, a blog devoted to the exploration of the murder ballad tradition in folk and popular music, and her poetry has appeared in a variety of journals, including Tin House Online, Salamander, The Pinch, and West Branch. Visit her website: https://www.cindyhuntermorgan.com.

Hunter Morgan answered questions posed by Kara Dempsey '19 on April 3, 2019, when the Center for Poetry’s Spring Poetry Festival kicked off.

Kara Dempsey: April is National Poetry Month. What does that mean to you?

Cindy Hunter Morgan: Well, here at the RCAH, it means we kick off our spring poetry festival, which features three of our nation’s leading poets—Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Tyehimba Jess, and Franny Choi. But really, for me, every month is Poetry Month. We need poetry all year.

KD: Who are some of your favorite poets and why?

CHM: This is really one of the hardest questions for any poet to answer. The list is long and always growing. Maybe it’s more meaningful to tell you my criteria for inclusion in this sort of list. I admire poets whose work is, as Mary Ruefle says, “both arterial and venous. They give pleasure—or put a lump in our throats—and they make us think.” I want both in a poem: thinking and feeling.

KD: Does poetry play a role in improving the human condition?

CHM: I think so. Poetry, when it works best, avoids what is simple and superficial. It gives us a place where we can feel more fully human. We all want a world that has meaning in it. We all have some experience with grief. Poetry helps us understand what it means to be human—it draws us into a new awareness of what it means to live, to suffer, to hope, to grieve, to celebrate. Poems make our lives more available to us. Poetry confronts life, and poems, when they are working well, address the complexity of what it means to be human. It’s our job as humans to engage in this work. Emerson said, of writing poems and reading poems, that poetry is soul making. Wallace Stevens said, “The all-commanding subject matter of poetry is life.” The role of poetry is to deepen experience.

"The wonderful thing about poetry is that it allows us to

head into deep and difficult territory without

abandoning joy or hope."

KD: What is the main goal of the RCAH Center for Poetry? Talk a little about why the Center for Poetry important to RCAH, MSU, and the community.

CHM: We want to encourage people to read, write, and talk about poetry. We want to help people understand where and how poetry fits in their lives. We want to help introduce people to poems that feel real and alive to them. We want all to feel welcome and safe at our readings and workshops and special events. We want people to know that poems are there—are here—whenever we need help thinking about something that feels unanswerable. The RCAH Center for Poetry is a place where people can come and discover their own voices. We bring some of the nation’s leading poets to campus to share work that addresses what it means to be human, and what it means to struggle. That’s important for students, and it’s important for everybody.

KD: How do you see the Center for Poetry evolving over the next 10 years?

CHM: I think we’ll continue to grow. We certainly keep doing that. I’d like to think about how poetry might be used in all kinds of classrooms in service of all different discussions. I’d like to see the Center for Poetry engaged in various curricula. We love to collaborate, and I’d like to widen our collaborations. I’d like to work with the Library of Michigan. I’d like to do more work with Peckham and other community organizations. I’d like to do more workshops. I’d like to expand “Filmetry.” I’d like to see poetry featured in our graduation ceremony. I’d like to think about a poetry exhibit for the LookOut! Gallery. I’d like to bring more poetry to more people. People need poetry, and I’m always amazed how people come to appreciate this need after they’ve had some exposure to poetry that speaks to them.

KD: Can you talk about how the Center serves as a tool for students to explore the different kinds of poetry?

CHM: Sure. I think the poets we bring in for our fall writing series and our spring festival represent different voices, different aesthetics, and different struggles. When students hear these poets read their work, the students absorb the cadences and rhythms of different work. We take what we hear into our bodies, and what we hear influences how we write. The Poetry Center also has a wonderful library, which students are free to explore. We present a variety of workshops that help participants explore different ways into writing, and we post poems on the bulletin board outside the LookOut! Gallery every week, which gives everyone an easy way to read a poem.

KD: “Poetry” means a lot of things to a lot of people. How does the Center promote various cultural forms of poetry?

CHM: We promote various cultural forms of poetry by bringing in poets that represent all kinds of cultures and communities. I think our spring festival will help increase understanding of the history, role, and responsibilities of poets, and I think it will increase awareness of how oppressed and violated individuals have used art to overcome difficult circumstances. This year, we gave particular attention to poets whose work addresses disconnection and fragmentation, struggle, and resistance. Our visiting poets address important issues in their work: exploitation, oppression, invisibility, erasure. We also encourage our audience to seek out more books, attend more readings, and view more videos that are authored by or relate to the lives of minority writers.

KD: It’s been a difficult couple of years at MSU. How can poetry help us through the healing process, help us deal with the tough things going on in our community, such as the sexual assault crisis on campus?

CHM: Yes. We have much to reckon with. We’ve confronted and continue to confront serious issues, and many have stepped forward to speak about their own experiences with difficult conditions and circumstances: harassment, violence, exploitation, oppression, invisibility, and erasure. Some who speak are still feeling their way into their own voices. Others, likely, haul memories in silence. I think poets and poetry can help address the sense of disconnection and fragmentation many feel, and can help pull various communities together. Poets ply their work in service not just of “expression,” but in service of understanding. Poets address history directly and personally, and part of their art is in their ability to manage emotional complexity and avoid simplification. This is the kind of art and the kind of thinking we need at Michigan State to build a healthy climate and culture.

KD: So you really think poetry has the power to heal?

KD: So you really think poetry has the power to heal?

CHM: Yes. The wonderful thing about poetry is that it allows us to head into deep and difficult territory without abandoning joy or hope. Embedded in Apocalyptic Swing, one of Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s books that confronts violent racism and hatred, is “Jubilee,” a poem in which Calvocoressi urges the reader to “Bring your snare drum, / your hubcaps, the trash can lid. Bring every / joyful noise you’ve held at bay so long.” That’s about healing, to be sure. I also think poetry allows us to say what sometimes feels unsayable, and I think reading and hearing poetry can cultivate a greater sense of empathy and an increased ability to ask hard questions about what challenges others face. That’s a kind of healing, too.

KD: What is one thing you wish more people understood about poetry?

CHM: There are poems waiting for them. There are poems they will read that will feel like they were written just for them. There are poems inside them waiting to be written. Also…poetry is for everyone. It is not just for “poets.”

KD: If someone came up to you on the street and asked you what your favorite line of poetry is... what would you reply?

CHM: Well, it’s hard to pull one line from a whole poem. Usually that one line needs the rest of the poem attached to it to deliver its full punch. I’m not sure I have a favorite line, but I have always loved the end of Galway Kinnell’s poem “First Song”: “…and the song woke / His heart to the darkness and into the sadness of joy.” There’s such tenderness in that, and a real awareness of what Keats said is the one thing needed to write good poetry: a feeling for light and shade.

For more on the RCAH Center for Poetry, visit http://poetry.rcah.msu.edu.

Madeleine Gorman ’17 reads in the RCAH Center for Poetry library.

Photos by Dave Trumpie.

The Residential College in the Arts and Humanities at Michigan State University is where students live their passions while changing the world. In RCAH, students prepare for meaningful careers by examining critical issues through the lens of culture, the visual and performing arts, community engagement, literature, philosophy, history, writing, and social justice. RCAH is situated in historic Snyder-Phillips Hall, where students learn and live together in a small-college setting, with all the advantages of a major university. For more information, visit rcah.msu.edu, email rcah@msu.edu, or call 517-355-0210.

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/RCAHMSU/

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/rcahatmsu/

Twitter https://twitter.com/RCAH_MSU

YouTube https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpfDHNy0ws5nxgaL9v1xMGw